Summer has become an increasingly important piece of the resort business model. In the first part of this series (SAM January 2019), we introduced some data points about the rapid growth of summer visitation in mountain communities, gave an overview of what those growth figures look like, and did some brief comparisons to winter data.

In this second installment, we’ll go deeper into the numbers, using our benchmark of winter data for context, and discuss some of the nuances in the data that make straight comparisons difficult. Since lodging inventory issues are now impacting the increasingly-busy summer, we’ll present our view of the rent-by-owner marketplace, and discuss why this is a significant, broad-reaching issue for the industry as a whole—one that requires a holistic approach to understanding and regulating.

Just Do It?

Typically, winter resorts view visitation, lodging, activities, and special events as keys to the growth of summer. But not just any activities and events will do. Resorts typically seek to introduce the emerging summer product to the consumer without weakening the high-value winter message.

Others may have a stake in the game, too, and a similar aim. Somewhere in the background (and often at the forefront) is a marketing entity, usually in the form of a DMO (destination marketing organization), and perhaps a town or county government. These entities may have a significant investment in a winter-centric image and messaging, and they don’t want to weaken those.

Of course, some ski resorts, such as those near national parks or with significant lake systems nearby, have a genetic code built around year-round tourism. But those resorts and communities whose economy revolves around winter usually aim to incorporate the summer experience into their well-established winter brand, rather than changing the brand to match the summer experience.

Learning from Aspen and Vail

Not being a marketer, I explored this idea with two of the best in our industry: Christian Knapp, CMO of Aspen Skiing Company, and Chris Romer, president and CEO of the Vail Valley Partnership.

In Aspen and Snowmass, where the new Lost Forest is an award-winning marquee attraction during the warm season, the DMO has taken its position as a wilderness experience in winter and expanded it to summer, preserving much of the brand attraction while bringing in a new type of visitor.

Knapp says that the Aspen Snowmass development teams spent a long time making sure that the project “embraced the natural setting” to which their winter clients were accustomed, and were careful to ensure that the logos, color schemes, and the attractions themselves fit into the landscape and preserved that wilderness experience. In addition, the project was almost entirely on Forest Service land, making it a prime example of capitalizing on the easing of land use restrictions since 2014 to the benefit of summer growth.

Romer believes that successful resorts need to develop a brand platform that is season-agnostic, with marketing tactics varying by season, but offering a consistent set of core values, value propositions, and message, regardless of time of year. That’s what has taken place in the town and resort of Vail, where a wide variety of summer events has transformed the town and surrounding areas seamlessly to a year-round destination.

Both these mountain destinations have built incredibly strong summer visitation numbers that have risen dramatically in the past seven to 10 years, but also remain leaders in winter sport—a clever feat indeed.

That’s not the only successful strategy. In the Northeast, for instance, there are examples of resorts that balance unique summer and winter messages. Some of these put forth summer fun and autumn leaf-peeping messages followed by a highly competitive ski message, to the largest consumer markets in the country, without confusing the market.

However the messaging is being handled, the summer message has been spreading like wildfire, with astronomical growth for that season. But there is little evidence (yet) that summer guests are hearing the winter message. And vice versa. There’s been some increase in the ‘crossover’ guest, but those consumers who make it a habit to visit mountain communities in both summer and winter continue to make up the minority of visitors, leaving a lot of potential to be tapped.

The Climb to Occupancy Parity

With lodging the single largest in-destination expense for travelers, we at Inntopia study the performance of that sector to better understand the overall performance of destination travel and consumer behavior.

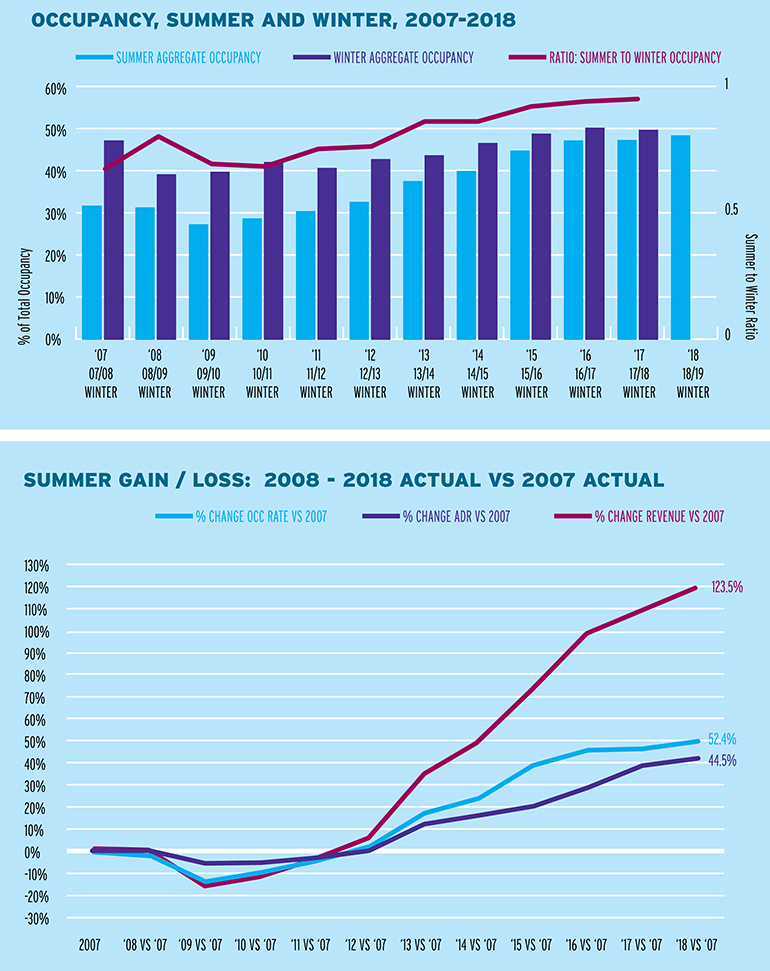

Without question, summer has been the big story. Summer occupancy rates at mountain destinations have been steadily climbing, both against themselves and against winter occupancy levels, since 2009. In many Western destinations, summer occupancy now equals that of winter.

This did not happen by accident. Driven in large part by concerns about the sustainability of communities on winter-only revenue, DMOs, town and county governments, resort companies, and other community stakeholders have invested significantly in increased and improved cultural events and activities, and the creation of summer season “destination magnets.” In the West, the easing of Forest Service land-use restrictions starting in 2014 and the support of local ordinance changes have also helped make this possible.

The graphs above show how summer business has grown, both compared to winter (top) and to itself since 2007 (bottom). The short story: summer occupancy is now on par with winter (top), and occupancy, rate, and revenue have climbed dramatically (bottom).

The graphs above show how summer business has grown, both compared to winter (top) and to itself since 2007 (bottom). The short story: summer occupancy is now on par with winter (top), and occupancy, rate, and revenue have climbed dramatically (bottom).

Post-Recession Growth

Prior to 2009, the record for summer season occupancy at Western mountain destinations was 31.7 percent, set in 2007 just prior to the recession. At that time, summer occupancy was 67 percent that of winter occupancy. What followed were two consecutive years of decline in summer occupancy, to a low point of 27.3 percent in 2009, as consumers reeled. But the changes to consumer behavior that came out of the recession worked in favor of destinations.

Modest recovery in 2010 reflected economic rebirth as consumers looked for ways to invest in travel and adventure, but did so with fewer discretionary dollars. In that light, summer mountain travel was an attractive offer, as it provided relatively inexpensive adventure in select—and sometimes elite—communities. Rates were about half the price of winter travel to the same destinations.

What followed was an unbroken eight-year run of occupancy growth in mountain communities, averaging gains of 6.5 percent year-over-year (YOY), including a 14.9 percent YOY gain in 2014 and 12 percent gain in 2015. At the same time, winter occupancy also increased, but at an average pace of just 2.7 percent, resulting in a strong summer gain against winter.

And now? Summer occupancy in 2018 set an all-time record of 48.3 percent, a stunning 52.4 percent gain from the pre-recession high of 31.7 percent in 2007. But this is only half the story.

Summer vs. Winter

The other half of the story is room rate, which we touched upon in our first installment. Room rate for summer has grown dramatically since 2007. Even with the post-recession dips, it has experienced a strong average YOY gain of 4.8 percent, and a 12-year gain of 44.5 percent since summer 2007. The rate at destinations we track through our DestiMetrics service have risen to $237 per night, up from $164 per night. When taken in context with the occupancy gains noted earlier, overall revenue from lodging in summer is now 123.5 percent higher than it was in 2007, and 165 percent higher than in 2009, in the midst of the recession.

Even so, despite these dramatic gains in summer occupancy and near-parity between the seasons, winter remains the primary revenue driver in mountain communities. That’s because room rate during summer and winter have increased at nearly the same pace over the same period relative to each other. As a result, the room rate for summer is only about 62 percent that of winter.

This seasonal disparity in rate fuels summer growth. Lower prices invite a broader demographic to the communities and introduce potentially new year-round guests who could become intrigued by the winter product after sampling summer. Yet the crossover, year-round guest to mountain communities remains somewhat elusive.

Another noteworthy point: Until now, destinations and service/lodging providers in the less-mature summer market have faced fewer challenges regarding rate, infrastructure, staffing, workforce housing, and other issues that plague the winter season. But as summer occupancy nears winter peaks, those challenges are growing in the summer, too. Chief among them is inventory.

The Rent-By-Owner Conundrum

Traditional discussions about lodging inventory have focused on the recently declining volume of units available within the professionally managed sector, driven by economic forces and market shifts that resulted in empty pipelines and owner attrition. As post-recession inventory stabilized, and recovered in the early teens from its sudden decline from 2008 to 2010, the rent by owner (RBO) marketplace moved from a nascent disruptor to a full-fledged market force and booking channel. Its impact on not only mountain destinations, but on all travel segments globally, cannot be overstated.

The RBO marketplace has taken the professional model of property management and thrown it a curveball. With homeowners suddenly able to market, sell, and fulfill their properties without the intervention of a professional property manager, inventories that had only just recovered from the aforementioned economic forces began to once again drop as homeowners opted for the less expensive, though less supported, channel of RBO.

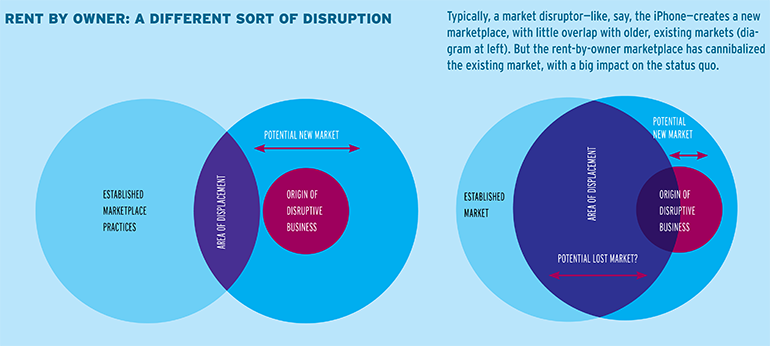

But this was no ordinary disruptor. A traditional market disruptor introduces a new product to the marketplace, say, an improved “widget.” In contrast, the RBO marketplace displaced the existing widgets from their normal sales channels and moved them to a new marketplace, dispersing a finite amount of inventory across a broader spectrum of distribution channels. The initial result was not only a decline in professionally managed inventory, but also a loss of control of inventory, reduced tax dollars, less understanding of capacity, and more (which we’ll get to shortly).

Almost simultaneously, homeowners not previously in the rental pool started taking advantage of the ease of the RBO platforms and added their units to inventory, creating a new, direct competition for property managers.

The Broader Impact

But this isn’t a story only of property management—it’s one of holistic impact.

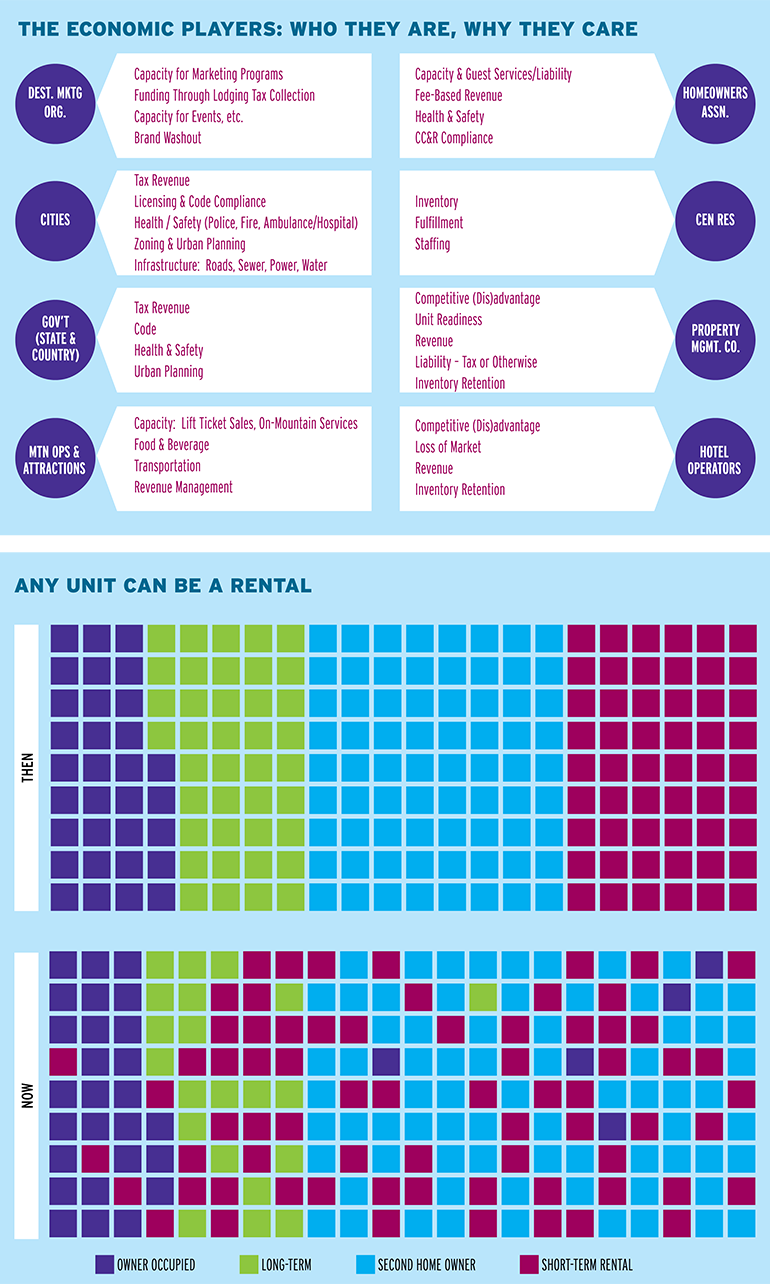

With the RBO market has come justifiable concern around town health and safety, lodging tax collection, loss of branding and image, infrastructure capacities, code compliance, urban planning, and the comfort and quality of life of local full-time residents. A balancing act, to be sure, and one that needs to be understood.

The single largest problem about the RBO presence is one of quantification—it’s incredibly difficult to measure what you cannot see. And in many cases the RBO market has had a significant head start on codification / compliance, putting jurisdictions and their constituents on the back foot.

In response, some jurisdictions reacted with an outright ban on RBO rentals, while others went to work on writing them into local code and zoning guidelines. Still others have yet to take action, though those remain fewer and further between.

But what has become clear is that entities ranging from state governments to local hoteliers all have a significant stake in a holistic approach to understanding the housing market. We advocate that all members of the community get involved in fleshing out and normalizing the rent by owner marketplace so that it can become a positive contributing factor in the community, or else the negative impacts will persist.

Housing Issues

So, what does this RBO trend have to do with summer rising? The resulting flux in the market is seasonally agnostic, and the impact is being felt across the industry. From a service provider or supplier point of view, one key impact is to workforce housing.

In the usual lifecycle in destination towns, as existing inventory became tired, much of it moved to workforce housing—the retirement home of destination inventory. But as RBO marketing and platforms matured, owners of those units jumped on the opportunity to put them on the open market to drive lucrative nightly rentals rather than lower-return monthly or seasonal leases. That eliminated a large part of the workforce housing inventory.

The impact on seasonal workforces has been dramatic. Increasingly, towns and resorts are relying on a workforce that must commute from elsewhere. This is particularly challenging in mountain communities, which are typically isolated and hard to reach. In general, purpose-built resorts are at a greater disadvantage than mountain ski towns, for both summer and winter operations.

But importing labor from “down the street” is not a viable long-term solution, either, as town boundaries and prices creep into those communities and make them unsuitable for workforce housing. It’s now becoming common for towns to incent construction of, or conversion to, workforce housing, often with the support of mountain operators that are most impacted. (See “Employees Need a Home,” page 46, for more.)

So, while there are clear challenges to both winter and summer coming from the prevalence of RBO, it’s good to see many towns working to resolve the situation holistically. It’s important to normalize this disruptive force so the industry can move forward with continued growth.

The conceptual diagram above represents both the original resort housing model (top) and current situation. Initially in purpose-built resorts, housing types were clearly defined and situated. In the current world, housing types are frequently intermingled.

The conceptual diagram above represents both the original resort housing model (top) and current situation. Initially in purpose-built resorts, housing types were clearly defined and situated. In the current world, housing types are frequently intermingled.

Gazing Into the Future

But what’s to come for summer in the mountains, and indeed year-round mountain tourism? With environmental threats such as warming coming into play, can we convert winter skiers to summer event-goers, or will we even need to? In the next installment we’ll look at the talking points from the first two and suggest what the future of summer visitation to mountain ski communities might look like in five to ten years.

Between RBO, only moderate new inventory, and traditional economic forces, what will happen with rates and capacity, and have we hit a price ceiling? Is there a tipping point where constant high visitation becomes too much for local homeowners? In an economic downturn, will summer or winter be hardest hit?

We’ll discuss all of that and more in Summer Rising, Part 3, in the May SAM.