Ski area terrain expansions large and small appear to be on an uptick in recent years, from Deer Valley’s massive planned 3,700-acre addition (see “Skiing Double,” p. 77) to smaller but impactful expansions at mom-and-pop mountains, like Wisconsin’s Trollhaugen—and they’re getting the attention of the skiing and riding public.

“If I say, ‘I’m going to make more snow,’ people will say ‘yeah, whatever,’” says Waterville Valley GM Tim Smith, who is overseeing a phased master plan at the New Hampshire resort that started with the 2017 debut of a new lift and 10 new trails on a second summit called Green Peak. “Expanding by 45 acres was that thing you could yell from the rooftop and people would pay attention.”

Of course, terrain expansions aren’t always just about the marketing opportunities (though that’s certainly a benefit, says Smith).

A major driver for this uptick in ski area terrain additions is obvious: the need to increase capacity to meet the demand for winter sports—U.S. skier visits have exceeded 60 million for an unprecedented three consecutive winters.

“We believe the number of skier visits in the country is limited by the available capacity,” says Pete Williams, director of mountain planning for SE Group, which works with ski areas on permitting, planning, and design. “The theory is, if you doubled the capacity, you would see twice the number of skier visits we’re seeing today. I don’t think we’ve heard of anyone who’s done an expansion who didn’t see a visit increase.”

A terrain expansion can benefit a ski area in a variety of ways. It can further diversify terrain, attracting different skier demographics by adding more beginner, advanced, or intermediate trails. It can motivate destination skiers to extend their stay, which can increase ticket sales on non-peak days. Or, for some ski areas, it can turn a local’s hill into one worth traveling for.

“Virtually all ski areas sell out on their peak days,” says Williams. “So, if you can figure out ways to bring people in midweek, that’s the holy grail of everything. You’re not only trying to increase your overall capacity [by expanding]; you’re trying to make your mountain more interesting.”

Smith says Waterville Valley needed to expand to stay relevant. As surrounding resorts grew, Waterville became a smaller resort by comparison. With a planned addition of 140 acres of terrain, new spaces for events and dining, and a two-stage gondola that will connect the resort’s Town Square to Green Peak’s base and summit, he anticipates that the resort will become a travel destination.

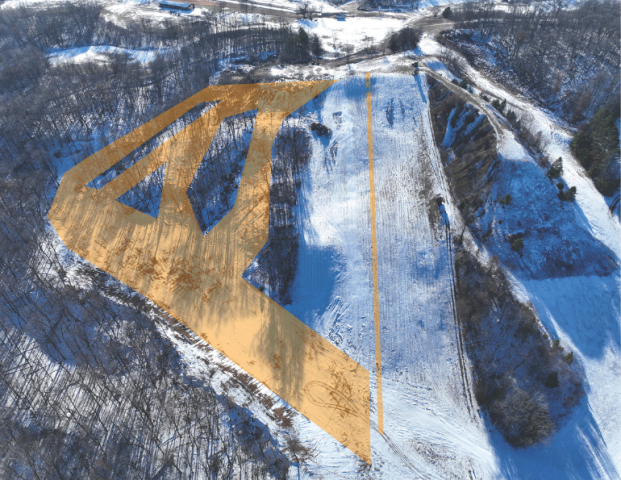

To update and expand an old terrain pod, Trollhaugen, Wis., added several new trails with snowmaking and replaced a rope tow with a quad chair.

To update and expand an old terrain pod, Trollhaugen, Wis., added several new trails with snowmaking and replaced a rope tow with a quad chair.

Plan Ahead

Ski area operators who have undergone even small expansions stress that it’s a herculean undertaking. Construction is often planned in multi-year phases, and it can take five years before a shovel even hits the ground—which is important to understand when considering such a project.

Financing the expansion. Figuring out how to pay for the project (often multi-millions of dollars) is the first and most obvious task. Waterville Valley was able to secure a small loan of around a million dollars to get projects like lift relocation, engineering work, and trail cutting started while working to secure a federally backed Small Business Administration (SBA) loan. Securing a loan can be challenging when there aren’t physical assets that the bank can repossess in the event of default.

Regardless of the funding source for an expansion project—some may lean on creditors, like a real estate investment trust, while others might have a capital reserve they can use for a loan downpayment—preparation is key.

Heading to the bank with quantitative data and breakdowns about anticipated revenue, visitation, and depreciation can make all the difference. Talking with owners, employees, and members of the community often helps shape these predictions.

“It starts with an idea, and then the concept comes together,” says Smith. “What else can I do with [putting] the lift up there? I can expand my night skiing. I can get more race programming in. I can put more competition programming in.” This all equates to potential revenue you can take to the bank, so to speak.

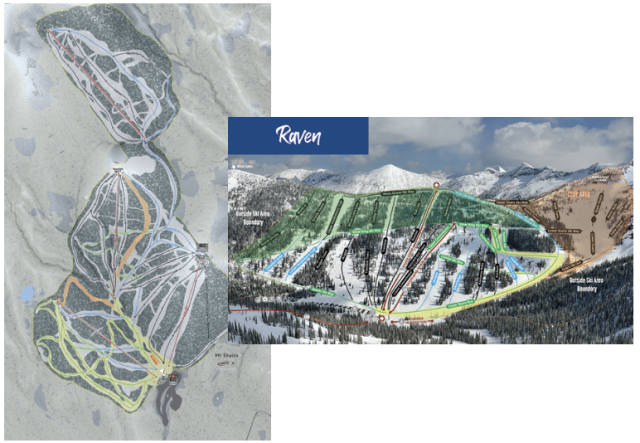

Left to Right: The Gray Butte expansion at Mt. Shasta Ski Park, Calif., (top pod at left) added roughly 200 skiable acres and 650 vertical feet; A new lift at Whitewater, B.C., brought an additional 123 acres of terrain and 535 vertical feet in 2023-24 (green shading), and another 60 acres of previously backcountry terrain for 2024-25 (orange shading).

Left to Right: The Gray Butte expansion at Mt. Shasta Ski Park, Calif., (top pod at left) added roughly 200 skiable acres and 650 vertical feet; A new lift at Whitewater, B.C., brought an additional 123 acres of terrain and 535 vertical feet in 2023-24 (green shading), and another 60 acres of previously backcountry terrain for 2024-25 (orange shading).

Permitting

Both acquiring funding and permits are tricky, time-consuming processes. Understanding the permitting process timeline is almost a prerequisite to obtaining a loan if an operator wants the project to proceed as quickly as possible, according to Smith. Otherwise, it’s possible to get caught up waiting for the lengthy permitting process to unfold.

“Permitting can take many years,” says Smith. “At the same time, establishing the financial ability to do a project can take as long, if not longer. So, you get into a bit of a chicken and egg scenario.”

That’s one reason Waterville Valley’s team approached the Forest Service before even inquiring about a loan.

Community outreach. Permitting is a complicated subject. It varies by state and county, and depends on land ownership and local environmental concerns. During Mt. Shasta Ski Park’s recent expansion, several tweaks to its plans, including lowering a lift terminal to minimize light pollution beyond a ridge, were required to obtain permits. The team at the Northern California ski area also had regular meetings with the county planning commission leading up to the project to mitigate concerns about public pushback.

“[The county supervisors] thought for sure that environmentalists would come out and protest and stop it,” says Mt. Shasta Ski Park general manager Jim Mullins. “They were concerned about the [Indigenous communities] and regional ecology center.”

Much of this concern was sparked by a multi-year legal battle the city and Siskiyou County had faced when the local Winnemem Wintu Tribe and an activist group opposed the Crystal Geyser Water Company’s plan to reopen a bottling plant near Mt. Shasta.

“But,” says Mullins, “when it came down to the final reading, everyone endorsed our project.”

He attributes this success to the community outreach that the resort did in advance. Furthermore, in such a small ski community, it’s no surprise that Mullins and his colleagues had personal relationships with the various concerned stakeholders—many of whom are also Mt. Shasta regulars who couldn’t wait to ski the roughly 200 acres of lift-accessed terrain the resort would be adding on Gray Butte, an area above the existing terrain that increased the ski area’s vertical drop by about 650 feet. And those relationships helped eliminate what could have been a major roadblock.

In the end, the ski area agreed to place an interpretive sign explaining the cultural significance of Gray Butte at its summit, per a local Indigenous tribe’s request. Forty acres of old-growth forest was set aside for conservation and potential light pollution concerns were addressed, meeting the requests of environmental groups.

Environmental concerns. As with any project that disturbs a natural ecosystem, environmental permits that consider things like stormwater mitigation, watershed impacts, the effect on vulnerable species, and rehabilitation, are a major part of the equation. Becoming familiar with local and state regulations, or better yet, working with a consulting firm that specializes in similar projects, can help ease the process. In some cases, certain regulatory agencies can even be bypassed.

For example, Mt. Shasta went through a state-run environmental quality review but bypassed the National Environmental Policy Act permitting process since its expansion was on the resort’s privately-owned land.

And Wisconsin’s Trollhaugen, which added several trails and replaced an existing rope tow with a fixed-grip quad chairlift on property that it was already operating on, was able to eliminate the need for a state Department of Natural Resources stormwater mitigation permit by keeping the size of disturbed earth to less than one acre. That feat was cleverly done by cutting trees as close to grade as possible and leaving the stumps in place, thereby not disturbing the earth and retaining the root systems, which help to mitigate erosion.

Had they removed the stumps, the land would have been classified as “disturbed,” and the ski area would have exceeded the one-acre maximum and been required to obtain a stormwater mitigation permit.

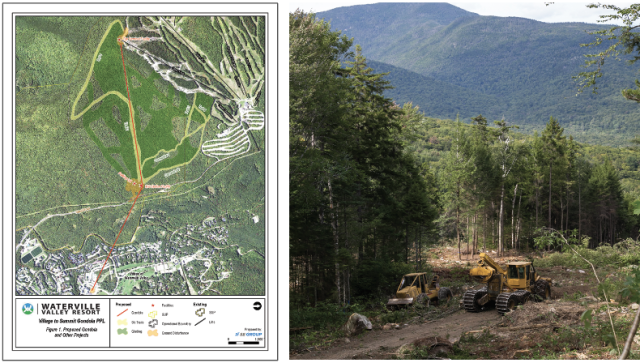

Left to Right: Waterville Valley’s (N.H.) second Green Peak terrain expansion proposal includes 140 acres of skiable terrain (light and dark green shading) in addition to the 45 acres added in 2017, a two-stage gondola connecting Waterville’s Town Square to the Green Peak base and summit (red line), and more; Trail blazing underway at Waterville Valley.

Left to Right: Waterville Valley’s (N.H.) second Green Peak terrain expansion proposal includes 140 acres of skiable terrain (light and dark green shading) in addition to the 45 acres added in 2017, a two-stage gondola connecting Waterville’s Town Square to the Green Peak base and summit (red line), and more; Trail blazing underway at Waterville Valley.

Cutting Trails

Most operators already have a relatively clear vision of the trail layout from the initial walk-through and permitting processes, but once the actual trail-cutting begins, the project starts to become a reality.

Tree work. Many operators have found mutually beneficial ways to work with logging companies and mills to minimize, or in some cases offset, their costs. Trollhaugen worked with a local logging company that paid the ski area for access to timber and permission to thin on the backside of the property. While it didn’t completely offset the expansion project’s cost, it didn’t hurt.

“We basically told them what we wanted cut and allowed them access to thinning on the back ends of our property,” says Trollhaugen general manager Jim Rochford. “That project would’ve taken our staff probably two months, but it took them and their machines two-and-a-half days.”

Mt. Shasta Ski Park worked out a similar deal, selling the timber that had been cleared for the new terrain to a local mill.

Erosion control. Of course, with any construction project where a natural surface will be altered, managing stormwater to meet regulations and prevent erosion is critical. An important component of a successful expansion project is working with an engineering firm that can help determine how to maintain the pre-project hydrology by using buffers, swales, water bars, culverts, and other best management practices (BMPs). But while stormwater mitigation and treatment measures can be daunting, the extent to which they’re required is very site specific.

At Trollhaugen, for example, since the new terrain was naturally skiable and required minimal dirt work, the hydrology remained the same and only required minor stormwater control measures. Where the ski area did have to deal with stormwater mitigation was in its parking lot expansion, which increased the overall footprint of an impermeable surface.

More than New Terrain

Thinking beyond the physical terrain is also key to a ski area’s expansion success. If there’s no room for additional skiers to park or enough staff to operate lifts, all the additional terrain in the world won’t matter. Most of these considerations are pretty obvious—the need for increased parking capacity, additional grooming and snowmaking equipment, additional staffing and whether applicants are even available, water availability and how to get it to the new terrain, required electrical infrastructure, and so on.

British Columbia’s Whitewater Ski Resort, which added 123 acres of terrain and 535 vertical feet with the addition of a new lift in 2023-24, had to add a voltage regulator to manage the increased electrical demand, while at Mt. Shasta, an additional lift crew was hired to operate the new chairlift. Some ski areas even shuffle existing management staff to create space for one person to focus on the expansion project itself.

Hazard mitigation. Some considerations are less obvious. Whitewater, for example, had to find ways to manage and restrict new access to out-of-bounds avalanche-prone terrain from the new lift.

“You’re not just cutting runs, you’re grading between them so people can ski, and you’re working with your snow safety team to come up with safety management plans for that terrain,” says Whitewater outdoor operations manager David Michael. “That’s another big part of the resort that has never been managed by ski patrol before. So, you’re determining where the signs will go and what the hazard mitigation will look like for this area.”

Despite the addition of signage and ropes to deter unprepared skiers and riders from leaving the resort boundary, the likely increase in traffic to the newly-lift-accessible backcountry terrain was a concern. To address it, this season Whitewater extended its ski area boundary to include the area of Ymir Bowl that’s now accessible from the lift (previously only accessed via skinning), which it was able to do since the additional 60 acres of terrain is part of a “controlled recreation area” lease from the government. This will allow ski patrol to perform avalanche mitigation and enforce terrain closures, which it couldn’t do when the terrain was outside of the resort boundary.

Return on Investment

For the budget savvy, calculating the return on investment based on anticipated additional revenue generation is a relatively simple task. But for many ski areas embarking on a terrain expansion project, there’s more to it than simply the bottom line.

“We’re hoping for a return in seven to eight years, but if it takes more, we understand,” says Trollhaugen’s Rochford. “This is a part of the infrastructure that isn’t going away. We’ve been here since 1950, and my family has been a part of the process since 1967. And so even if it takes 15 years, it’ll still be the stamp that my generation was able to put on this area to make it better.”

At Mt. Shasta Ski Park, completing the expansion fulfills the dream of previous owner Ray Merlo, who died in 2020. And at Whitewater, the additional lift has resulted in the already-scarce lift lines becoming non-existent, adding value in the form of an improved customer experience.

“[Expanding] is one of the most exciting things you’ll ever do, but it’ll also be one of the hardest,” says Waterville’s Smith. “And you’ve got to prepare yourself for years to understand what you’re about to get into. You have to be bursting out of your seat, so pumped that you’re willing to work 20 hours a day for six months. And if you’re not willing to do that, don’t do it.”