Bob Dylan once said, “There is nothing so stable as change,” meaning that everything changes at some point, or change is constant, which is true. Also true is that foregoing what is firmly established, i.e., stable, in favor of fluidity and adaptability can be hard. However, change is necessary to improve, evolve, and innovate.

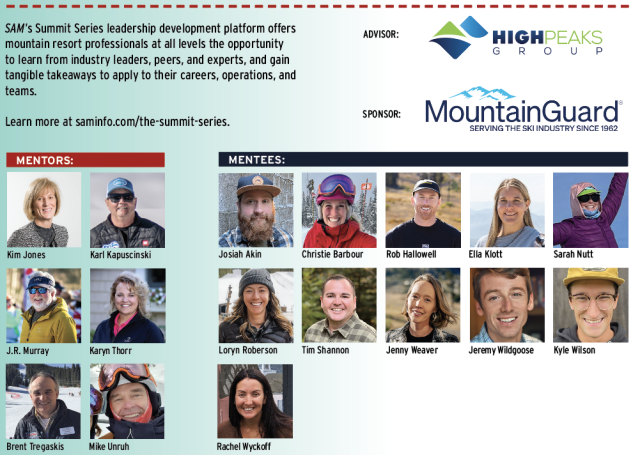

“If we want to improve, then we have to change. Period,” said Boyne Resorts senior vice president of mountain operations Mike Unruh during a fall SAM Summit Series course titled “How to Change When Change Is All We Do.” Unruh was one of six Summit Series mentors to share insights about how to manage change with 11 aspiring industry leaders, aka mentees, in the program.

The other mentors that participated in this course included Kim Jones, vice president and general counsel, WinSport Olympic Park, Calgary; Karl Kapuscinski, CEO, California Mountain Resort Company; J.R. Murray, chief planning officer, Mountain Capital Partners; Karyn Thorr, COO, Crystal Mountain, Mich.; and Brent Tregaskis, president and general manager, Eldora Mountain Resort, Colo.

Things Have Changed

The pace of change has accelerated significantly in recent years. Keeping up, not to mention trying to get ahead, is challenging, which makes it all the more important for ski area leaders—from supervisors to the person in the corner office—to embrace change and instill the need for it as part of the company culture.

On a macro level, the North American ski industry as a whole is very different now than it was, say, 30 or 40 years ago when the industry was more mom and pop, according to Murray. “It was family, it was hobby, it was fun. And now it’s big business,” he said, “and it didn’t used to be.” That evolution has touched every aspect of the business.

When Tregaskis started in management back in the mid-1980s, “not much changed year to year,” he said. “You weren’t looking for the next best thing. And nowadays, our company’s always looking for the next best thing.”

It wasn’t long ago that change felt more reasonably paced, “not necessarily rare, but certainly less frequent than it is now,” said High Peaks Group founder and organizational development expert Paul Thallner, who is also a primary advisor and coach for the Summit Series. “We could manage change-related tasks in a silo—if it was a marketing issue, we’d put the marketing team on it; if it was a manufacturing issue, we’d get the engineers on it.”

“Those days are kind of over,” he said.

Now, it’s important for organizations to “develop a process whereby they are open to, engaged with, and able to change,” said Thallner. “This includes bridging our efforts within a coherent framework as opposed to working in silos—bringing in resources and people from around your organization to help with solutioning and managing change is what most organizations are doing.”

Team Effort

With that coherent framework in mind, one of the biggest takeaways from any lesson about managing change is the importance of including people in the process, from ideation to decision-making to execution, especially those who will be most affected by a change that’s being considered. Without inviting them in and welcoming their input, these people will likely be the most resistant to any proposed change. By including them, however, they may become champions of that change—and the process will likely be improved as a result.

Learn by listening. When a ski area gets a new owner, for example, at least some things are probably going to change, which the incumbent staff may or may not welcome. Kapuscinski and his company now own four ski areas, having acquired three since 2021. His aim is not to homogenize the four resorts, but to take advantage of efficiencies to help all four be more successful, which requires some changes.

Instead of showing up and telling staffers what is changing, he’s found success by involving people early on and discussing changes before they’re made—and this can lead to the realization that change may not be necessary.

“A lot of times you’ll find when you get people’s input, you don’t go exactly the way you thought you were originally going to go,” said Kapuscinski. “And is it really necessary to do it just to do it, or just because somebody 500 miles away thought that was the best way of doing it? So, you learn a lot by listening and by involving others in the decision-making process.

“The decisions or the practices that have gone the best are when more people get involved early on.”

Solicit input. Staff members who have good ideas and valuable opinions may not feel comfortable sharing them with leadership, either because of the company culture (more on that in a bit) or they’re just not that type of person. In the latter case, Unruh encouraged asking more questions to pull ideas and opinions out of them. “Very few of us like being told what we’re going to do to change, but if we’re involved in it, then we can get excited, then we can get motivated,” he said.

Another benefit of involving people in the process is it can help them understand why a change is being considered.

“The question to ask a lot of times with team members is: What is the problem we’re trying to solve with changing something?” said Thorr. “And, usually, if a team member understands what that problem is and the pinch points of that problem, they’re on board with trying something new because they’re living the problem.”

Kapuscinski said involvement is also key for people to understand the process, the goal, and “what it’s going to take to get from point A to point Z.”

These interactions can happen during meetings or even off-site sessions, but they should be something real, not a token exchange.

Communication among staff—namely which departments must interact about changes being made—has evolved, thanks in large part to technology. “We are now seeing teams communicate differently and more often than maybe they used to,” said Thorr. With new lift technology, for example, “the IT team, who maybe wouldn’t have spoken with the outside operations team so often—now they’re really working together on upgrades and making sure all of the infrastructure and communications are working right.

“So, we’re bringing teams together now in different ways than we had to before, or maybe had the opportunity to do so before. I see that as a good thing,” she said.

To Kapuscinski, one of the keys to successful change management is transparent communication from beginning to end. “It’s always been about transparency, it’s always been about communication,” he said.

Company Culture

Good communication and transparency are the pillars of developing and maintaining a culture of trust within a company. It allows for leaders to address things openly and for managers and supervisors to feel comfortable managing up.

“First of all, I think everybody will agree that culture is key to everything,” said Unruh. If your culture creates an environment where change is resisted, and people fear change and fight change, “something’s wrong with your culture, and change isn’t going to work until you fix the culture.”

At Mountain Capital Partners, embracing change is an inherent part of the culture, according to Murray. “We just need to be telling people that if you’re working for our organization, every year is a different year, a different season. Everything changes. The weather changes, personnel changes. We are in a state of change. And people need to start hearing that and understanding that is the mindset, maybe, of the organization,” he said, so when there is a change, it’s not a surprise.

Building trust. Thorr thinks that “culture has a lot to do with building trust over time with people throughout the organization, at all levels, in all roles.”

Of course, for leaders to foster a culture of trust they need to be good listeners, too. How can good ideas get circulated if the boss isn’t willing to make time to hear them?

“You need to have a culture where people don’t mind coming to you and know their ideas are not going to be rejected immediately,” said Tregaskis.

Murray agrees that staff members need to feel comfortable approaching leadership and asking for a few minutes of their time.

“Don’t ever stifle that,” he advised. “Even if you’re busy, because people will come up to you as the boss and they’ll say, ‘I know you’re busy. I know you’re busy.’ And I would always look at them and go, ‘I’m not too busy for you. What’s on your mind?’”

Talk About It

From a leader’s perspective, making time for staff and working with them on their ideas encourages them to manage up. It typically takes courage for staff to approach their boss with an idea—but staff must also take the right approach to managing up, which is a nuanced situation depending on the boss’s personality and communication style. Are they casual or rigid? Can you just walk into their office, or do they require a formal calendar invite?

In general, though, Murray said it’s important to be prepared for the boss to say “yes” to your request for time to talk about your idea. Before you ask for the boss’s time, plan how you’ll introduce the idea and frame the change you’d like to suggest. This will help earn buy-in.

“Whatever you lead with, don’t say, ‘I want to change all the lesson times,’” for example, he said. “Don’t start with that. Start with, ‘I have an idea that I think we can get more people on the hill to learn to ski and enjoy their day.’ Now everybody’s head is shaking ‘yes.’”

What’s the objective? What is this change going to mean either for the guest or others? “Have all of your background ready, but stay super high-level executive summary,” said Unruh, who also relayed the importance of allowing the leader you’re speaking with to ask questions. “Let me ask the things I want to know, and you’re way more likely to get a yes from me.”

The suggested change also needs to fit within the construct of the resort’s overall stated direction, as well as its limitations. “I need people to understand what our company’s priorities are and what our strategic objectives are, and tie it into that,” said WinSport’s Jones. “I’ve had lots of people bring forward their great ideas, but they don’t align with what our current priorities are, and we only have so many resources.”

Don’t be afraid to bring outside-the-box ideas, she said, but make sure they can be tied back to your resort’s priorities.

Learn from the Past, Build for Tomorrow

It’s fairly common for people to not see the value of change, especially when what they’re doing now works just fine. Thallner discussed what he called “selective preservation,” which involves “learning from what’s worked in the past, but also letting go of those things that are either no longer relevant, haven’t worked, or just could end up being noise,” he said.

Thallner also reminded everyone that change often requires a shift in mindset. More specifically, Jones explained that part of a manager’s job is “helping people understand the difference between strategy and operations,” she said. “When you’re talking about operations and people being stuck in a way of doing things, that’s a very operational mindset.”

Jones suggested having a dialogue with people and teaching them about strategic thinking, even having off-site sessions to get away from the operations and into “a strategic mindset” to help them understand strategy, “because strategy is the reason that you’re ahead,” she said. “You’re not changing because the operations are broken. You’re changing because there’s a strategy that’s driving development.

From Paul Thallner: How to Stay Afloat During Times of Change

1. Recognize that change is constant. Don’t treat change as an episode or something that’s necessarily foreseeable. It is happening all the time, all around us.

2. Proactive reinvention. Break it before someone else does. In other words, we have to try new things and ensure that what we’re doing stays ahead of either competitors or customer needs. If you think that doing things the same way forever is going to be OK, you’ll probably get passed by. Use your resources to experiment before someone else comes up with the new thing.

Change is a process, not a project.

3. Selective preservation. There’s a delicate balance between resting on one’s laurels and learning from the past—good leadership is understanding the difference. Learn from what’s worked in the past, and let go of the things that are either no longer relevant, haven’t worked, or are just noise.

4. Winning while walking. Instead of simply identifying a problem and fixing it, we must also build for tomorrow. Work on the things right in front of you while also planning ahead, thinking downstream, anticipating challenges, building organizational resilience, and being ready for whatever the future might hold. Some of it we can predict, some of it we cannot. But it’s important to be prepared.