Ski areas have been ambitiously addressing climate change for the last decade—and some for much longer than that. The industry’s largest resort operators, Boyne Resorts, Powdr, Alterra Mountain Company, and Vail Resorts, have all pledged to become carbon-neutral by 2030, and many smaller-scale operators have bold emissions goals as well.

Right now, there isn’t a cost-viable renewable energy solution to every emission-producing activity at a ski area. Diesel-powered grooming machines need to operate daily. Buildings must be heated, and the lights must be kept on. Never mind the scope 3 emissions in your supply chain.

Enter: Renewable Energy Credits (RECs) and carbon offsets, mechanisms aimed at mitigating the environmental impact of a business’s carbon emissions. Ski areas have invested heavily in RECs and offsets in recent years. But the efficacy and validity of both have come under increased scrutiny, in some cases, with notable reverses of opinion.

CHANGING TACK

In 2006, Aspen Skiing Company (ASC) became the first ski area operator to offset 100 percent of its electricity use through the purchase of RECs. The company purchased 20,000 RECs for about $42,000, which was enough to cover the energy use at its four ski areas, three hotels, two athletic complexes, and a golf course. With the purchase, ASC could claim 100 percent of its electricity was from renewable sources.

False promise? If that sounds fishy to you, you have company. A year after ASC’s REC purchase, ASC senior vice president of sustainability Auden Schendler publicly declared the company had made a mistake investing in RECs. Schendler had concluded that the relatively low price of the RECs purchased—a small fraction of Aspen’s annual energy bill—meant the investment was unlikely to spur any significant production of more renewable energy, and therefore unlikely to slow the accumulation of greenhouse gas (GHG) levels in the atmosphere.

This is the crux of the argument against RECs made by Dr. Mark C. Trexler, an expert involved in the first carbon offset project in 1988, and others. Trexler has suggested there is no evidence that the voluntary REC market has lowered carbon emissions. REC purchases, he has said, are unlikely to lead to increased renewable energy production. Therefore, a significant portion do not result in actual mitigation. Moreover, Trexler has argued the effectiveness of RECs varies depending on the specific regulatory environment, market conditions, and the overall commitment of governments and industries to promoting renewable energy.

Boyne Mountain’s 1.7 MW on-site solar array was built in 2022.

Boyne Mountain’s 1.7 MW on-site solar array was built in 2022.

The value of local control. In the years following Schendler’s about-face on purchased RECs, ASC has focused more on developing its own renewable energy projects—some of which are supported by REC purchases. Why would ASC sell RECs from its energy projects if it considers the RECs it purchased in 2006 a mistake? Presumably, because it has direct control over how the REC funds are spent, unlike most such purchases.

For example, in 2012, ASC invested nearly $6 million in a project that converts waste methane from the Elk Creek Mine, a coal plant in Somerset, Colo., into usable “carbon negative” electricity. That project generated $100,000 to $150,000 in revenue per month from electricity and carbon-credit sales to Holy Cross Energy, effectively paying for itself, according to a 2021 progress report from ASC.

Following a natural decline in the volume of the waste methane, the project will no longer produce power, but rather convert the remaining waste methane to more abundant but less potent CO2. It will continue to make money selling methane destruction credits into the California cap-and-trade market, according to the Aspen Snowmass website, where the project is called a “rare example of a functional carbon offset—because without the sale of the credit, there would be no financial incentive to flare the methane.”

New capacity. As that quote implies, not all credits actually create new renewable energy sources. Some merely allocate renewable energy that is already in the grid or, as in Aspen’s Elk Creek case, create a “functional carbon offset.”

Those other cases often have some value. But as far as growing the supply of renewable energy is concerned, the key principle is additionality.

How can anyone know when renewable energy sources are truly being added?

“Not all RECs are created equal, and it is important to understand what your goals are, the differences in RECs, and the mechanisms that exist in procuring or receiving them,” says Fritz Bratschie, director of sustainability at Vail Resorts.

When it comes to sorting the “good” from the “bad,” though, Erika Kazi, a sustainability consultant who has worked with several ski areas, says there are few regulations on REC programs. “Even if you have the best intentions,” she says, “that money [spent on RECs] could just be going into some guy’s pocket, and not actually to the projects that you think you’re investing in.”

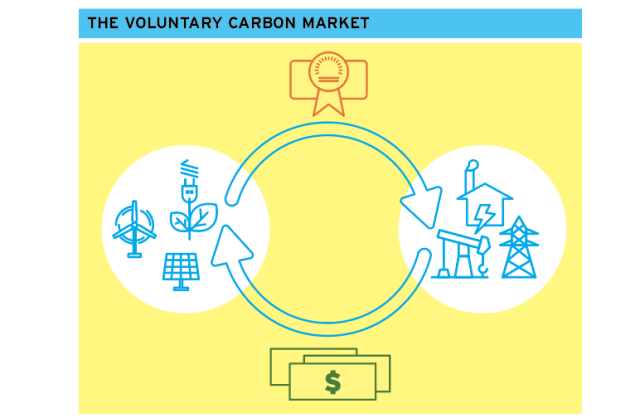

A new Joint Statement of Policy and Principles for Responsible Participation in Voluntary Carbon Markets (VCMs) from the U.S. government, described by U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Janet L. Yellen as “an important step toward building high-integrity voluntary carbon markets,” aims to improve upon the situation.

And many feel that RECs still play an important role in supporting renewable energy generation and meeting net-zero emission goals. According to research published by Morgan Stanley, VCMs are expected to grow from $2 billion in 2020 to around $250 billion by 2050.

THE 101

A primer: RECs and offsets differ. RECs were invented in the 1990s as a tool to stimulate the renewable energy market. Organizations can purchase RECs to claim ownership over renewably generated megawatt-hours without having to produce the electricity themselves. So, for instance, when a solar farm sells the power it generates to the electrical grid, it can also sell credits for that power to corporations and other buyers. In theory, the purchase of RECs supports the production of more renewable energy.

Because electricity received through a shared utility grid is not distinguished by its method of generation or source, RECs are also a tool to assign ownership of renewable energy and substantiate consumers’ renewable energy use claims.

Offsets, on the other hand, deliver investments in carbon sequestering projects, such as reforestation or the capture of methane from landfills or other initiatives. The idea is to “offset” your emissions by contributing financially to projects that remove or reduce an equivalent amount of greenhouse gases from the atmosphere.

To be valid, offsets must be able to prove the amount of emissions they are keeping out of the atmosphere. Similarly, the net efficacy of REC purchases can be difficult to quantify. Both strategies have come under increased scrutiny in recent years, mainly for a lack of third-party oversight and credible auditing.

WHY BUY?

Support for renewable energy. Vail Resorts has purchased RECs as part of its strategy to achieve net-zero emissions by 2030. The company has focused on investing in large-scale renewable energy projects that replace fossil fuels in the grid and, where possible, in the direct development of local renewable projects that contribute to local grids where the company operates its resorts.

Its largest renewable project is the Plum Creek Wind Project, an 82-turbine wind farm in Nebraska that has been online since June 2020. VR is one of the project’s three “power offtakers.” Construction on the Elektron Solar Project, an 80-megawatt solar farm being constructed 60 miles west of Salt Lake City, was completed earlier this year. VR is one of its six participating customers. “These projects provide renewable electricity that powers our operations, and RECs are created from the renewable energy production, which we claim toward our goals,” explains Bratschie.

For all that, it’s difficult to know how much VR benefits directly from these particular investments, though the benefits could be substantial.

Boyne Resorts has adopted a similar approach regarding its 2030 net-zero emissions goal. The company is focused on bringing additional renewable resources into the grid in the areas where it operates, says Tom Bradley, vice president of sustainability. Those projects include a 1.7 MW on-site solar array at Boyne Mountain Resort, Mich.,which was added in 2022, and multiple smaller solar projects currently in development in Maine, home of Sunday River and Sugarloaf. All have “associated RECs” that will be retired on the company’s behalf to claim the renewable energy.

Associated RECs, i.e., those sold with their associated electricity, are referred to as bundled RECs. These are often part of the financing structure of new renewable energy projects, and thus typically understood to support the addition of new renewable energy to the grid. Unbundled RECs are sold separately from the electricity produced by their associated renewable energy source, and may come from existing projects so do not necessarily result in the development of additional renewable energy.

That said, Boyne has purchased those, too. “Whether electricity comes from on-site or off-site resources, we know that new renewable resources can take multiple years to come online and start producing clean electricity,” Bradley says. Rather than wait on future projects, in 2020, Boyne purchased enough RECs from a wind farm in Texas to cover 100 percent of its energy use.

“We understood that these would be considered unbundled RECs, but feel it is better to do something now while we explore more options to obtain bundled RECs from future projects that add renewable energy to our grids,” Bradley explains.

“It’s a challenge to build enough clean renewable power on-site at our resorts, so we recognize that RECs from off-site resources are critical,” he adds.

Boyne Mountain’s 1.7 MW on-site solar array clearly adds new renewable energy production to the area. It’s more difficult to ensure (or prove) that RECs do the same, though that could change in the future.

Boyne Mountain’s 1.7 MW on-site solar array clearly adds new renewable energy production to the area. It’s more difficult to ensure (or prove) that RECs do the same, though that could change in the future.

Powdr was a large purchaser of RECs early on, when the alternative energy industry was in its earlier stages of evolution, says vice president of sustainability Raj Basi. “With fewer other options at the time, an investment in the nascent industry was a compelling reason to buy RECs that aligned well with our mission of supporting innovation,” he says. “We still believe in RECs as a way to support the expansion of alternative energy, but we are buying fewer today as we continue exploring new frontiers of alternative energy.”

One of Powdr’s newest alternative energy solutions is the advanced biomass boiler system going in at Oregon’s Mt. Bachelor. The system will not only replace fossil fuel as a primary energy source for heating, but it will also generate a small amount of electricity. In addition, the system will divert wood that would otherwise have been burned in open slash piles, thereby further reducing both carbon emissions and local wildfire risk.

A useful stop-gap. Dawn Boulware, vice president of social and environmental responsibility at New Mexico’s Taos Ski Valley, echoes Basi’s sentiment that RECs provide a useful stop-gap measure while a company looks for more direct ways to reduce its emissions.

The process to measure your energy use and develop and implement projects and plans to reduce that usage and associated emissions “takes a while,” says Boulware, “so we decided that while we’re working to reduce our direct carbon emissions, we’re going to take action now for those emissions that we can’t immediately reduce by other means.”

For example, Boulware says that part of the effort to achieve LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) certification for the newly constructed Blake Hotel in 2017 included the purchase of Green-e certified RECs, because the building did not have a direct source of renewable energy, and Taos’s local energy provider was not incorporating renewable energy into its grid at that time.

Taos Ski Valley also invests in offsets, says Boulware. Both RECs and offsets serve as self-taxation, she adds. “This is internal motivation for us to reduce our emissions, because basically we’re paying double for our energy usage,” she explains. “Whether it’s your electricity or fuel usage, not only are you paying your bills, but you’re also paying to offset your use of that energy.”

Businesses purchase carbon credits to offset their GHG emissions. In theory, the purchases support the generation of new renewable energy, while the credits retired on behalf of the buyer assign ownership of the energy.

Businesses purchase carbon credits to offset their GHG emissions. In theory, the purchases support the generation of new renewable energy, while the credits retired on behalf of the buyer assign ownership of the energy.

SORTING GOOD FROM BAD

RECs are a “Band-Aid on sustainability efforts,” says consultant Kazi. “Offsetting your footprint is a great temporary option while you sort out your programs at your resorts, but that’s all it is: temporary and non-exhaustive.”

“Reduction action should come first,” says Geraldine Link, the National Ski Areas Association director of public policy, with RECs and offsets as secondary options to further mitigate a ski area’s impact.

What to look for. When purchasing offsets, it’s important to make sure they are third-party certified, says Boulware. Taos works with the firm Climate Action Partners to find high-quality projects.

Ski areas looking to purchase RECs or offsets should consider the energy source, the location of the project, the environmental impact, and the purchasing agreement itself, advises Basi. For example, “Resorts might want to prioritize projects in close geographic proximity to be part of a larger effort, either by creating a critical mass to boost the industry in that particular area or to help fund the development of additional local sources of energy,” he says.

As a rule, Basi adds, “The purchase of RECs should lead to the development of new projects that would not have occurred without the financial support of the purchase.”

“RECs are an interesting topic,” he adds. “It is one of an increasingly large set of sustainability options, and there is no standard solution.”

“The idea is that you utilize RECs and offsets to mitigate the impacts of your emissions in the short-term as you work toward reducing or eliminating your carbon emissions in the long-term,” says Link.

“RECs may not be perfect, but they are the only way to ensure that a company is purchasing power from renewable sources,” she says. “When you get into the RECs and offsets realm, do your research on what you are getting, like you would do for any purchase. And, finally, don’t give up hope—your climate action can make a difference.”

Correction, Sept. 26, 2024: A previous version of this article erroneously stated that NSAA public policy director Geraldine Link agreed with contributor Erika Kazi's characterization that RECs are "a Band-Aid on sustainability efforts." Link clarified, "I do not agree with Ms. Kazi’s characterization of RECs as a “Band-Aid” on sustainability efforts. Many ski areas are taking on projects to reduce GHG emissions and electricity consumption in their operations, and they are also purchasing RECs to address Scope 2 (purchased electricity) emissions and support renewable energy development. In the 2023-24 season, our Climate Challengers reported that RECs contributed to a 20 percent reduction in scope 2 emissions, which results in net emissions of 91,701 MT CO2e. This is significant. I would encourage your readers to review NSAA’s 2024 Climate Challenge Report, which will be published in the coming week, to better appreciate the role that RECs play in helping ski areas meet their renewable energy goals.”