Ski areas consume a tremendous amount of fossil fuel to heat their facilities, which comes at both a financial and an environmental cost. Two resorts on opposite ends of the country—Mt. Bachelor in Oregon and Jay Peak in Vermont—are investing in different technology that will help to reduce those costs while providing benefits beyond what is realized by the resorts.

Both systems are unique and designed to dramatically reduce propane consumption and carbon emissions. And both projects serve as examples of what ski areas across North America can do to heat their facilities more efficiently while also making a positive impact locally and regionally.

Mt. Bachelor:

Burning Wood for the Greater Good

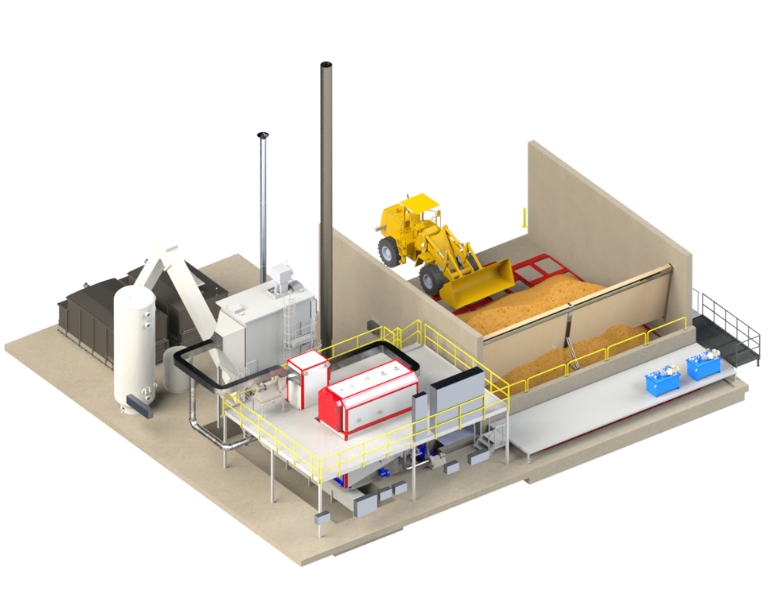

POWDR-owned Mt. Bachelor has set the wheels in motion to upgrade its current heating system to an innovative biomass boiler system that will run entirely on raw, minimally-processed wood from wildfire mitigation and forest management activities conducted by the United States Forest Service (USFS) in the surrounding Deschutes National Forest. The system is scheduled to be operational for the 2024-25 ski season. Site work and construction began in June on a facility with the potential to house the biomass system, contingent on Department of Environmental Quality approval.

Once implemented, it’s estimated the boiler will cut both heating costs and carbon emissions by approximately 40 percent, inclusive of the existing local emissions from the burning of slash piles during ongoing wildfire mitigation activities.

“One of POWDR’s core commitments within its Play Forever campaign is to protect the environment and support our community,” says POWDR vice president of sustainability Raj Basi. “Bachelor, like POWDR, is committed to helping ensure that future generations have the same ability to enjoy nature as we do, and that’s what we’re doing all of this for.”

Planning. Initial discussions with Wisewood Energy—a Portland-based provider of high-tech biomass energy systems—about upgrading Bachelor’s existing heating system involved replacing the resort’s propane boilers with a wood pellet boiler, but a desire for increased efficiency pushed the team to look at options for a centralized system that would allow for the utilization of a minimally processed, local fuel source.

“As the project evolved, we realized we might be sitting on a huge opportunity to utilize local wood fuel from the Deschutes National Forest,” says Tanner Fields, sustainability specialist at Mt. Bachelor. “The project is kind of a holistic partnership between the USFS, their contractors, and ourselves to source the wood fuels locally, store them off site, and deliver them on an as-needed basis to our facilities.”

Currently, Bachelor heats different buildings around the mountain through a number of separate boiler systems and air handlers, which can pose its own logistical and maintenance-related challenges. The new 4,094 MBH (1,200 kW) system will be a closed-loop, centralized heating system that will utilize sub-surface PEX piping to deliver hot water to the existing heating systems, potentially tying in up to nine buildings and the heated sidewalks around the base area and simplifying operations.

Emissions—including gases and particulates—will be treated by both multi-cyclone and electrostatic filtration systems, removing approximately 99 percent of total emissions, resulting in effluent carbon and particulate matter concentrations that are comparable to propane.

Local fuel. The Deschutes National Forest requires year-round wildfire prevention tactics. Typically, brush and small trees are cleared and burned in slash piles to inhibit the spread of fires. The new boiler system will utilize approximately 1,200 tons of raw wood material from these local forest management activities annually, and burn it more efficiently while emitting less CO2 and particulate matter than would burning it in the slash piles.

A third-party contractor will collect and chip the green wood, which will then be delivered to the ski area and burned without additional processing. During 2023 alone, the USFS is permitted to treat 47,000 acres, which equates to 470,000 tons of raw wood material—enough to heat the ski area for 350 years. Additionally, utilization of the locally-sourced raw wood will eliminate the need to have fossil fuels trucked in from further away.

“This is going to be another demonstration of different ways that we can use small diameter material that we produce from the forest every year,” says Bend-Fort Rock district ranger for the Deschutes National Forest Kevin Larkin. “It’s something that we have a hard time finding a productive use for. Now we’re helping to utilize material that would otherwise not have much benefit. It’s a great thing.”

Multiple stakeholders. Another unique aspect to this project is that it involves local, state, and federal interests and investment. Grants to offset the cost of the project have been offered by the USFS, Deschutes County, and the Oregon Department of Energy.

“[The project is] not only inter-government but it’s inter-agency,” says Basi. “There are a bunch of different angles here that governments are very interested in supporting. There are grants to get the project going that are not specific to construction—it’s just ‘get this going because we want to see what happens and how this turns out.’”

In fact, according to Basi, a key takeaway from the project so far is the importance of involving other stakeholders early on, because they not only provide support but also help to shape outcomes and find solutions.

The project will create approximately 16-20 short-term jobs for the construction and installation of the facility and system, and up to six long-term jobs for the contractors who will be processing and delivering the wood.

Operation and maintenance of the system will be minimal, according to Mt. Bachelor director of base operations Ryan Gage, who anticipates a facilities maintenance technician will need to dedicate less than two hours a day to checking the system and removing ash bins. This self-sufficiency is largely due to an automatic “walking floor” system, which will continuously feed the boiler with biomass and maintain the necessary heat and internal pressure.

While this forward-thinking approach to using otherwise wasted biomass as a fuel source is innovative, the team hopes the project will lay the groundwork for other ski areas and businesses in the future.

“There are other businesses—not necessarily ski areas—that are off the grid, and under the Inflation Reduction Act there’s a push to use alternative forms of energy,” says Basi. “So, I think collaborating with local communities is going to be even more important with the coming legislation. And this is a roadmap for ways to [use] alternative [sources] of energy.”

Jay Peak:

Smart System

On the East Coast, PGRI-owned Jay Peak has installed a 3-mW electric boiler intended to heat the 176-room Hotel Jay, Conference Center, Pump House indoor waterpark, restaurants, and retail spaces.

How it works. The boiler at Jay Peak utilizes a telemetry system that tracks the price of propane and compares it against the price of electricity through the Independent System Operator (ISO)-New England grid, automatically switching from the existing propane system—which consists of 12 three-million BTU propane boilers—to electricity during periods of time (with one hour being the minimum) that will provide a cost savings.

This process will also add a load to the electrical grid during times when the grid doesn’t typically have enough demand to support generation from renewable resources, allowing providers to continue pumping renewable energy into the grid. During times when there’s too much power on the grid, Jay’s system will switch to electricity, reducing the amount of power and allowing the renewable sources to kick in.

“We actually have a lot of [renewable energy] generation,” says Vermont Electric Co-op’s government affairs and member relations manager Andrea Cohen. “We have a lot of solar and some wind, but the actual demand for electricity is pretty low [near Jay] because there aren’t a lot of people. So, Jay using more electricity through this project would be very positive from a grid stability perspective.”

In fact, about 75 percent of the Co-op’s electricity is generated by renewable resources, although the goal is to increase it to 100 percent by 2030, notes Cohen. With Jay Peak’s added load, there will be more of an opportunity for renewable energy providers to contribute energy.

The draw added to the grid from the electric boiler will be significant, thanks in part to the high draw required to heat Jay’s waterpark and hotel.

“The outside temperature was -46 [degrees Fahrenheit] back when it was cold here in January,” recalls Jay Peak communications manager Mike Chait. “And it was 86 degrees and humid inside the waterpark, so you know there’s a lot going on there.”

(Recent upgrades to the existing infrastructure allow for the capture of spent heat generated by ice production for the Ice Haus indoor skating arena that can then be redirected to the heating facilities in the waterpark, further helping cut heating costs and emissions.)

Savings and operation. The $1 million project is estimated to provide a net savings of around $200,000 in heating costs annually, reduce CO2 emissions by 2,500 tons each year, and reduce propane consumption by 450,000 gallons annually—60 percent of the entire propane consumption required to heat the Hotel Jay amenity complex.

And since the new system is basically an electric boiler with tracking software, three main circulation pumps, and a heat exchanger, all of which tie into the existing heating system, additional man-hours required to maintain and operate it will be minimal. According to Jay Peak’s director of facilities and resort services, Andy Stenger, they may add one more maintenance person who is proficient with HVAC and electrical work to the team, but not much will be required aside from annual or bi-annual maintenance.

The new system utilizes existing storage space in the basement below the waterpark, adjacent to the current boiler system. The equipment is all on site, and the team completed a successful factory startup on Aug. 1.

Numerous collaborators. Like the biomass boiler project at Mt. Bachelor, the project at Jay also has a number of collaborators and financial backers: Medley Thermal; the Vermont Electric Co-op; Efficiency Vermont; Vermont Gas Systems; the State of Vermont (through the capital investment program); and the State of Massachusetts—all of which provided financial assistance through grants, leaving Jay Peak with only 30 percent of the bill.

The project was born in 2020 when DeltaClime Vermont, which supports “startup and seed-stage ventures focusing on energy and climate economy innovation in the energy sector,” approached Medley Thermal, which develops hybrid boiler systems, with the idea for the new system. Medley then began looking for propane consumers throughout Vermont before eventually landing on Jay Peak, one of the largest propane consumers in the region.

“A lot of what our team does is just try to find these happy coincidences where you have a large heat user near an area where there’s a lot of excess renewable energy,” says Medley Thermal founder Jordan Kearns.

Looking ahead, Antora Energy, which recently acquired Medley Thermal, has been working on thermal storage technology that will allow systems like Jay’s to utilize stored energy during times when it would switch to propane.

A model for others. Another theme the Jay Peak project shares with Mt. Bachelor’s biomass boiler: much of the big-picture optimism lies in the ability for other ski areas to follow suit with similar innovative ways to cut their carbon emissions—especially in an industry so dependent on the climate.

“It’s becoming increasingly important for industries and even individual homeowners to do what they can to curb carbon emissions to try to slow the weather changes we’re seeing,” says Stenger. “We’ve got an opportunity to make a big impact on the resort’s carbon emissions, and I would hope other industries and folks in the ski industry see what we’re doing and look at their own operation to see if there is something they can do. [This project] could be a sign of what’s to come for big facilities.”