Since the arrival of the pandemic in 2020, construction costs have soared 40 percent over a three-year period. Building prices climbed a colossal 19.92 percent in 2022 alone. This figure not only represents the highest percentage increase in U.S. history, but it is also 5.5 times higher than the 3.6 percent increase we usually see on an annualized basis. While construction inflation is coming down in 2024, construction costs remain sky-high.

These costs are taking their toll. Many needed capital improvement projects within the industry are caught between “can’t afford” and “can’t afford not to.”

This three-part series tackles construction costs from multiple perspectives: due diligence, “saving, by design,” and revenue growth. It offers real-world strategies to battle this trend and, more importantly, to come out on top. —J.A.

Good design sits alongside due diligence as the foundation for a construction project’s financial success. Let’s assume, then, that your team has done its due diligence and put a building program in place (as covered in part 1, “Due Diligence: The Financial Foundation,” SAM, May 2024). You’ve hired your design team and are considering options to bring a qualified pre-construction contractor onboard. Now, it’s time to put pencil to paper and design your project to meet core budget, quality, and schedule objectives.

First, we should define “good design” in the context of cost savings. A well-designed facility has no more or less than what it really needs. Good design is about balance and efficiency, not trying to build at the lowest cost possible.

Yes, some quality materials are less expensive than others, and you can build simply and still build right (more about that later). But there is no magic bullet to cut costs, which are driven by quality and the marketplace. Good design, though, can save you from spending on inefficiencies or on fixes after the fact.

Good design is also based on a realistic budget, not wishful thinking. For instance, with building inflation now coming down, it is all too easy to imagine that construction prices will fall back to where they used to be or that your project will hit the timing of the market just right. That is highly unlikely, since once prices go up, they rarely come back down. Never say never (I’ve seen construction costs drop once in my career), but don’t bet on it.

When commencing your design, plan for today’s high prices while developing a strategy to minimize the impact. The idea is to set a realistic baseline and build smart.

John Ashworth, AIA, is a third-generation architect and principal at Bull Stockwell Allen, specializing in concepting, feasibility, and the realization of four-season destinations. Bull Stockwell Allen has been involved in resort, recreation, and hospitality design and planning since its inception in the 1960s.

RIGHT SIZE

As part of your due diligence, you have hopefully developed a detailed building program, which is handy, but is only a starting point—a paper exercise referencing required building spaces and associated square footages, the interpretation of which is an art and not a science. Even the most thoughtful programs are often products of yesterday’s thinking about space planning, and/or a function of departmental “wish lists” that exceed what can reasonably be accommodated within the budget. A good design solution must therefore right-size the building.

There is no such thing as “one size fits all” with respect to program needs. The metrics for a destination resort will differ from those of a drive-to location in determining, for example, how many offices or how much space for a particular service is really needed. Brand, demographics, and expectations also factor into the mix.

Case study: Tahoe Donner. In anticipation of the need to replace a dated, 16,000-square-foot day lodge built in the 1960s, the Tahoe Donner Association commissioned conceptual space plans and a building program for a new facility. Located in Truckee, Calif., Tahoe Donner is part of one of America’s largest homeowners’ associations with more than 25,000 members. It operates a variety of amenities, including a public ski hill that skews heavily toward novice skiers.

The original programming and concept documents were drafted in 2018, a pre-Covid world after which everything turned upside down, including ski operations. The program suggested a replacement size of roughly 36,000 square feet—a tall order, even at “old world” prices. Living in a post-Covid world amid rising construction costs, the operator selected a design team and went to work right sizing the facility.

Shrinking to fit. As part of this process, the operator reviewed key business centers to prioritize the investment of its limited capital and set an overall budget, and the design team adopted newly evolving best practices geared to minimize building area requirements while improving operations. These practices included, for example, the adoption of new “Guestination” models (see “Building New ‘Guestinations,’” SAM, September 2022) that rely on technology, online purchasing, departmental consolidation, and the recognition that the outdoors is a great place to seat hungry skiers.

The team also combined the facility’s rental components around a centralized fleet to serve both ski school patrons and the general public. Separate and distinct lines of circulation extend around opposite sides of the equipment, allowing a consolidated staff to serve both populations in accordance with the demand. This approach eliminated the need for two rental locations and will facilitate a reduction in associated operation costs.

These efforts reduced the building size by more than 30 percent on paper, from 36,000 to 28,000 square feet. However, given the post-pandemic costs, even this smaller building, from a budgeting perspective, was never going to fly.

“Every time our contractor delivered an interim (building) estimate, the costs kept going up, up, and up,” says Tahoe Donner director of capital projects and facilities Jon Mitchell. “It was hard not to shoot the messenger, but it was clear looking around that no one in construction could predict where we would land nine to 12 months out. We had no choice but to dig deeper for further area reductions to get closer to the approved budget.”

Digging deeper. The challenge was to preserve the lodge’s operations potential and also protect its income potential. The association did not want something too small to serve the community long-term or to forsake improvements to the guest experience. The solution? To look at all aspects of the building, including building systems and assemblies.

This resulted in the removal of an additional 4,000 square feet. One “convenience” stairway was eliminated, and another was moved to minimize the construction of additional exterior building envelope. Given the Sierra’s high desert climate, the team also moved nearly 50 percent of the food and beverage seats outdoors and under cover.

While that percentage goes beyond industry norms (typically 20-25 percent in the West, post-Covid), the resort’s numbers justified the decision. Faced with a lack of demand on weekdays, maximum seating was only needed on the big weekends with favorable weather conditions that attract a high volume of guests, especially beginners.

With the new lodge currently under construction, Mitchell says, “We made the right decision to move forward. Sure, we lost a few bells and whistles here and there, but at the end of the day, and without adversely sacrificing quality, we achieved 95 percent of the vision.”

OUTSIDE IS IN

Outdoor dining spaces, which cost far less than conditioned interior space, are a boon to the industry. A new trend we call “transitional seating” is currently gaining momentum.

The Rosebrook Lodge at Bretton Woods, N.H., and the brand-new Aerie at Copper Mountain, Colo., both feature what we describe as three layers of seating: traditional indoor seating, covered indoor/outdoor seats (aka transitional seating), as well as tables open to the sky. The transitional zone is perhaps the most interesting, as it can provide heaters and additional wind protection, while extending the indoors out when weather permits. The cost advantage relative to indoor seating is significant. Even with all the bells and whistles, transitional seating can cost up to half that of indoor seating.

Design potential. Consider outdoor spaces as “outdoor rooms” worthy of as much attention as any space inside the building. Through creative programming and the incorporation of fire pits, live music stations, and enhanced outdoor food venues, the outside can easily become the “in” place to be.

From our perspective and based on a few projects currently on the boards, the industry is only beginning to unlock the potential of great outdoors space, where views and the experience can be designed to be like no place else. Calculating the correct number of seats to move outdoors draws upon climate, location/views, demographics, and imagination.

K.I.S.S.

When it comes to building design, all three of these new lodges exhibit a design strategy that my firm’s founder, Henrik Bull, referenced throughout his career. It’s called the K.I.S.S. doctrine, as in “Keep It Simple, Stupid.”

Roof design. For Henrik, and especially in snow country, simplicity began with a building’s roof design. Steep roof pitches can shed snow in a dramatic fashion, often endangering lives and property in the process. Ice dams and icicles and often incompatible gutter systems are also roof-related issues that require a host of costly and maintenance-prone solutions, including snow clips, snow guards, heat trace, and snow splitters. Dormers, gables, and other intersecting roof forms create valley conditions that require underlayment and additional metal flashing to prevent leaks. Even then, the valleys can be torn apart through glacial action or snow creep. In other words, complicated roofs are both dangerous and expensive.

It’s a little-known fact that the steep and complex roof forms that most of us associate with the mountains evolved when the great hotels and lodges were built by the American and Canadian railroads for summer use only, such as the Mount Washington Hotel or Yellowstone’s Old Faithful Lodge.

In comparison, a Swiss chalet has a simple, low-slope gable roof form, designed to keep snow on the roof to serve as insulation. The gable’s ridge provides protection from snow and icicles for family members entering below. Conversely, the traditional American colonial saltbox dumps snow right at the front door.

Truth be told, simple low-slope roof forms perform better in snow country, and without all the belts and suspenders. At Tahoe Donner, the roof slope follows the drop of the natural terrain, with its “kick-up” and internal drain system virtually eliminating icicles around the entire perimeter.

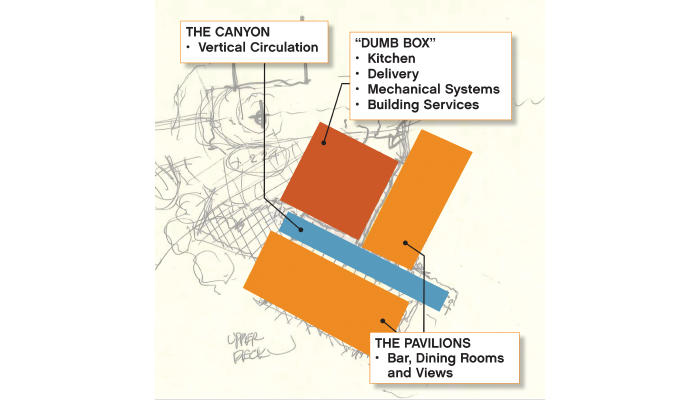

At Rosebrook, the roof is a single plane sloping to the rear where icicles and falling snow are of no concern. At the Aerie, the roof forms are simple sloped planes, or what we call shed roofs, designed so snow slides at the low end where it will drop harmlessly over the kitchen and other back-of-house spaces in the portion of the building we call the “dumb box.” These design choices save money by keeping it simple while minimizing facility maintenance costs.

BIG, STUPID, AND DUMB

Keep in mind as you move into detailed design and engineering that not all parts of a building should be created equally, and some parts of a building are more expensive than others.

The four construction trades with the biggest savings potential are: concrete, structural steel, MEP (mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems), and site work (including the requirements for utilities, excavation, and imported fill). These trades require careful assessment and ongoing review throughout the course of the project, as they are tied directly to cost, quality, operations, and the environment. There are no easy answers here, other than staying on top of decision-making in concert with your organization’s priorities and values. Additionally, initial costs should be viewed against the project’s schedule (time is money) and the available local workforce.

Non-public spaces. Another strategy to save real dollars: put money where the public will see and experience it and then spend as little as possible everywhere else. While this space is conceived as a simple square. It is not built with the dramatic post and beam, exposed heavy timber structural elements, that characterize the facility’s signature restaurant and bar space. Rather, it is built with simple stud framing, minimal steel and a relatively inexpensive, premanufactured “Trus Joist” or TJI system.

Public spaces. Even in public spaces, Copper Mountain considered costs. One trick: the resort utilized a “ladder” window wall system that allowed for the installation of attainable and easy-to-install nail-fin windows in lieu of a custom curtain-wall system. Other low-hanging fruit for cost savings include incorporating locally available materials, standard colors and dimensions for window and wall systems, simple and, if possible, off-the-shelf railing systems, and non-proprietary bidding.

THINK FORWARD

While we are not always good at predicting the impacts or success of new technology, we should always ask ourselves what’s next. Articles in SAM and elsewhere have documented how new technology and app-based purchases can reduce building area requirements, collapse departmental silos, minimize staffing requirements, and—under the most enlightened circumstances—improve the overall guest experience.

Operating costs. Ongoing labor shortages and the associated costs of operating a building should be considered as you finalize your design. Think beyond the initial construction dollars to consider what it will take to own, operate, and maintain a new facility over the next 20 or 30 years.

Energy and the environment should be part of this consideration. A geothermal-based mechanical system, for instance, will cost more up front, but, if viable, will have a relatively quick payback while being the right thing to do for our environment. Also, consider going all electric, not to save costs now, but to anticipate where we will be in the future.

When it comes to good design, everything adds up either positive or negative. An integrated approach is more critical than ever when looking at a project’s return on investment against today’s high construction costs.

What’s next. Due diligence and informed design create a strong foundation for a project, but there is one additional step to go beyond break-even on construction costs. Part three of this series will look at ways to maximize revenue as part of a development strategy to achieve a project’s ultimate financial success.